Note: Graphs and texts in blue are from the Cato Working Paper No. 35.

Note: Texts in blue are from the Cato Working Paper No. 35.

Now

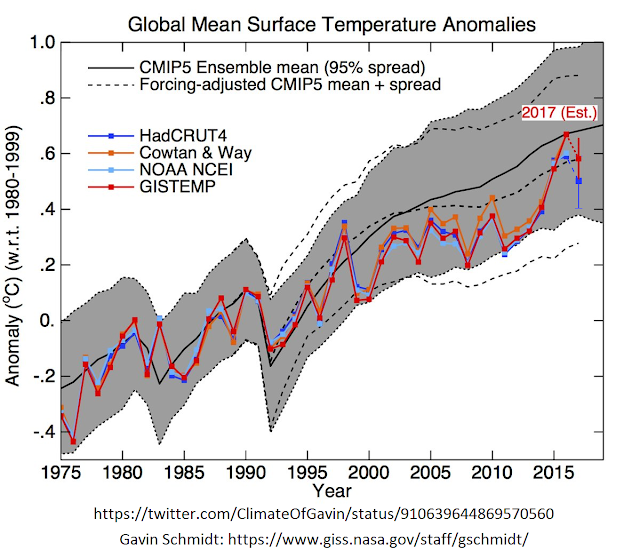

I am going to compare Michaels and Knappenberger’s

historical findings in their Cato Working Paper No. 35 with the 2017 NASA-GISS

observational data graph I found at Robert Fanney’s blog “Robertscribbler,”

presented below. You will be able to find it at the NASA website, located

here (click on "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change").

Chart

A: The black squares are the annual global mean average estimated temperatures

since 1880. Obviously NASA didn’t exist all the way back to 1880 so the older

averages were computed from data that were taken from various sources such as

the US and British Imperial weather services. The red line represents the

“Lowess Smoothing,” I haven’t the faintest clue what that means. The Blue I’s

represent uncertainty bars: 0.25 C spread (+/- 12.5 C) in the late 19th Century

(1892), 0.17 C spread in the mid-Twentieth (1948) and 0.10 C spread in the late

20th / early 21st Centuries (2009). The 2017 global mean temperature (not

shown) is estimated to be approximately 0.92 deg C above the 20th Century

average.

This

graph shows a cooling from 1880 to 1909, the a slight warming ‘til about 1945,

another slight cooling until 1976 ad then a consistent rise at roughly 0.2 deg

C per decade through 2016. There is a low point at 1992, the year after Mount

Pinatubo blew up. The 2002-2014 Pause is hidden in the annual means’ noise but

the Lowess Smoothing detects a shorter pause or at the very least a massive

deceleration.

Well we can use these temperatures to check Michaels and

Knappenberger’s plot of the NASA GISS temperature data and I’ve done so by

printing the above on an 8½ by 11, drawing gridlines straight across and

scaling to the nearest millimeter (half-millimeter if the square falls right

between two lines) to the nearest gridline. The temperatures are plotted not in

10th of a degree Celsius, but in hundredths of a degree. So I scaled off from

-0.5 to +1.0 and came up with a scale converter. I did the same thing from

Cato’s Figure 2 for the GISS multiyear trends, plugged everything into an Excel

spreadsheet, used the LINEST command to construct a trend, and down below are

the plots.

Chart B: The red line is the plot line of the multiyear decadal

trends I generated for the reference year 2015 from the 2017 NASA GISS

temperature records graph downloaded Sunday, October 01, 2017. The blue line represents the plot line of the multiyear

decadal trends. Note the red line is noticeably forward a year beginning about the

trend length of 40 years. Otherwise it is in reasonable close conformity to my red

line graph.

My plot shows the jump in trend from the 11-year trend length to

the 10-year trend length. This is the first year that the signal from 2015 has

made itself known to a much higher amplitude within the trends. All subsequent

years with their shorter trend lengths are probably excessively noisy.

Michaels and Knappenberger’s plot has that one year deviation that

I had noticed before, starting at about the 40-year trend length—it is ahead of

my plot by exactly one year. This is a fat-fingered error: either in the

authors’ Figure 2 graph, or in the stated year runs in its caption. The global

cooling from Mount Pinatubo was removed from 1992 to 1993! Any way let the

record show that the NASA GISS 2006-2015 trend increased from the authors’

value of 0.12 deg C per decade to the true value of almost 0.20. With errors

such as these and the others noted in Part 1, errors that I, a layman have discovered,

it really doesn’t inspire any confidence in me that they are doing rigorous

enough science---hard science---for it to pass peer review or auditing!

Now we are going to check the proper plotline against the IPCC’s

CMIP-5 forecast, as shown in the Cato paper. The multiple model runs were based

on historical data up to 2006 and the RCP4.5 scenario after that year.

Chart C: Cato’s CMIP5 model and NASA GISS 2015 data set runs

showing trends from 1951 through 2006 with reference year to 2015, with my NASA

GISS 2017 data set runs for and referenced to the same years. The purple line

is the multiple model-run mean, the cyan and spring green lines are the

model-runs’ 97.5% and 2.5% percentiles respectively. The blue line is Cato’s

trend plot from the 2015 NASA GISS data set and the red line is my trend plot

from the 2017 NASA GISS data set.

Again, this graph shows that the one-year discrepancy that I had

noticed in Figure 2 (Part 1) is proven. The peaks in the trends as computed by Michaels

and Knappenberger are in the 23-years’ trend length (1993-2015), instead of the

24-years’ length (1992-2015) as my NASA GISS plot (red line) shows and is

reflective of the actual global mean temperature low point in 1992 (see Chart

A). The authors’ GISS plot shows a continued low warming trend of about 0.12

deg C per decade whereas mine increases to 0.200 deg C per decade and close to

the multiple model-run mean (MMM).

Now to find out the source of the Cato paper’s discrepancy I

took their plotted NASA GISS values from Figure 2, and compared them to my computed

trends for the NASA GISS temperature records from 1950 through 2005 and

referenced to 2014. When I made a plot, my numbers and the paper’s numbers

became widely variant when running into the shorter trend lengths, so I won’t

belabor the point here.

So then what I did was reset their end years, 1951 and 2006, to

1950 and 2005 respectively, and kept my plot the same as it was in Chart B,

with an added year 1950 and the 2006 year dropped. The referenced year remained

the same throughout: 2015. And this is what I found in Chart D below:

Chart D: The Cato paper’s CMIP5 model and NASA GISS 2017 data

set runs showing trends reset to beginning in 1950 and ending in 2005 with

reference year to 2015, with my NASA GISS 2017 data set runs for and referenced

to the same years. “Annual years” are the years for the starting points of the

respective trends. End points for all trends is 2015. The trend lengths now

vary from 66 years (1950-2015) to 11 years (2005-2015). Explication of colored

lines are the same as in Chart C.

This adjustment achieves a much better fit for the Cato paper’s

model runs and GISS data set plot lines. The peak trends resulting from the

1992 global mean temperature low point are now where they should be. The Cato NASA

GISS trend plot (blue line) and mine (red line) are now in close conformity to

each other up to the trend length of 13 years and only diverge after that. This

is probably because Michaels and Knappenberger came up with an estimate for the

year 2015:

We have

also updated our AGU presentation [in December 2014] with our best guess for 2015 average temperatures.

The

actual NASA GISS global mean average temperature for 2015 was apparently higher

than the authors’ estimate, and the other actual data sets would probably show

higher 2015 averages as well. The gross errors that were introduced in Figure 2

(Part 1) and the discrepancies between Figures 2 and 3 are probably due to the author’s

stated updating without checking to make sure that their trend lengths in the

graph and stated run years in Figure 2’s caption were correct, as they are not.

Now

on to checking Cato’s Figure 3.

Chart

D: The Cato paper’s CMIP5 modified model set and the 2014 Hadley HadCRUT4 data

set (blue line) compared with the 2017 NASA GISS data set (red line) for all

trends with end year reference of 2014. Trend lengths begin with 65 years

(1950-2014) and end with 10 years (2010-2014). The Model set has been modified

according to the Hadley HadCRUT4 Method to reflect a blend of land surface air

temperatures and sea surface temperatures, and obtained from the University of

York website (http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~kdc3/papers/robust2015/index.html).

Explication of the model set’s colored lines are similar to those in Charts C

& D.

In

the above Chart, the NASA GISS trend plot line roughly parallels the HadCRUT4

line until about the 45-years’ trend length, then follows in close conformity

thereto until the 27-years’ trend length, whereupon the two lines diverge. Both

lines hit a peak at the 23 years’ (1992-2014) trend length—right after Mt.

Pinatubo blew up, after which they slowly descend roughly parallel to each

other until they hit a low point at 2005. This descent is indicative of a

steadily but noisily increasing mean of global temperature until 2002, where it

levels off, going into the Pause which ended in 2014. The parallel descent into

very low decadal trends indicates that Michaels and Knappenberger had

referenced their Hadley data set trends in their Figure 3 for the end year of

2014, and is not indicative of

fat-fingered errors at the Cato institute. It also means that Figure 3 is,

essentially, correct.

I

am unable to check Figure 4 owing to the fact that Christy’s data in Figure 1

went by annual five-year global mean temperatures and his corresponding data in

Figure 4 went by annual means as indicated in the two figures and their

captions. So I will compare the model forecasts with the observed temperatures

in Figure 1 instead.

Chart

E. The Cato paper’s CMIP5 Model set for the tropical mid-troposphere compared

with the 2015 Christy balloon data sets (red line) for all trends with end year

reference of 2015. Trend lengths begin with 40 years (1976-2015) and end with

10 years (2006-2015). The temperature data from the Model set and the balloon

data sets have been provided to the Cato Institute by Dr. John Christy of the

University of Alabama in Huntsville.

The

results are similar to what is seen in Cato’s Figure 4. The data from Dr.

Christy comport with the Figure 4 trends that run significantly lower than the

mean of the multiple model runs (MMM) and even below the 2.5th percentile line.

The plot line shown here also runs below the minimum for all runs from the

33-year to 23-year trend lengths. The plot line also confirms the sense of

Figure 4 in that the trends are running almost uniformly at 0.1 deg C per

decade. A caution noted here is that Christy’s observational data are from the

five-year running averages shown in Figure 1, so some noise has been eliminated

from the data. A comparison of this graph with Charts C and D shows that

through 2015, when the trends end outside the Pause, the tropical mid-troposphere

appears to be warming at a slower rate than is the surface, possibly giving a

greater differential between surface and mid-troposphere temperatures and

thereby allowing for more moisture-laden air to arise from our lands and seas

to supercharge our weather, although a caveatshould be noted that the tropical mid-troposphere

temperatures should be compared with the tropical surface temperatures and that

temperatures at altitude are expected to warm much less than the surface at

higher latitudes.

Conclusion

on Checking Cato’s Figures.

Although

Michaels and Knappenberger’s Figures 1, 2 and 3 appear to be correct, and their

discussion is for the almost the whole very well written, I cannot recommend

this paper to anyone without serious reservations because of the gross errors

they introduced into Figure 2 when they updated it for release of the paper at

the end of 2015. It would have been better they left the plot lines remaining as

they were in 2014, as they did for their Figure 3. They have also failed to do

another check, which is to compile uniform multiple-year trends, for example,

30-year trends going back from 1985-2014 to 1921-1950.

Well

I’m up to 2,000 words now. I will leave it for Part 3 to see if this paper has

held up under the increased temperatures of 2016 and 2017.

Filed under: Global Warming, Cato Institute